Book Review: 100 Baggers (Draft)

Jan 19, 2026

- Date Read: 2026-01-19

- Rating: 8.5/10

Summary

This book is about 100-baggers. It is study of stocks that returns $100 for every $1 invested.

This is a well structured book ; divided into two parts. In first part, Christopher gives stories and examples of companies which achieved 100 baggers. Then he goes into analysis of what is common between these companies and what we can learn from it and refine our search for 100 baggers with this approach.

I loved the book ; it is clearly written, full of real-world examples and logical breakdown of common themes between the 100 baggers stocks.

My Notes

Chapter 1 : Introducing 100-Baggers

- He introduces us to the famous book “100 to 1 in the stock market” by Thomas Phelps, where the original study of 100 baggers was done. Some of the key notes mentioned from that book:

Along the way, Phelps figured out a few things about investing. He conducted a fascinating study on stocks that returned $100 for every $1 invested. Yes, 100 to 1. Phelps found hundreds of such stocks, bunches available in any single year, that you could have bought and enjoyed a 100-to-1 return on—if you had just held on.

This was the main thrust of our conversation: the key is not only finding them, but keeping them. His basic conclusion can be summed up in the phrase “buy right and hold on.” “Let’s face it,” he said: “a great deal of investing is on par with the instinct that makes a fish bite on an edible spinner because it is moving.” Investors too bite on what’s moving and can’t sit on a stock that isn’t going anywhere. They also lose patience with one that is moving against them. This causes them to make a lot of trades and never enjoy truly mammoth returns. Investors crave activity, and Wall Street is built on it. The media feeds it all, making it seem as if important things happen every day. Hundreds of millions of shares change hands every session.

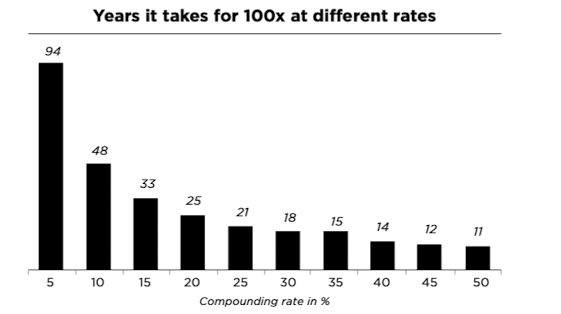

Phelps showed me a little table that reveals how much and for how long a stock must compound its value to multiply a hundredfold:

Phelps advises looking for new methods, new materials and new products—things that improve life, that solve problems and allow us to do things better, faster and cheaper.

Phelps is quick to add he is not advocating blindly holding onto stocks. “My advice to buy right and hold on is intended to counter unproductive activity,” he said, “not to recommend putting them away and forgetting them.”

- The last quote is a brilliant point. While holding is great, it is important to monitor this. In later chapter, Christopher also remarks that ideally he holds the stock for as long as ROE is growing, unless valuation (P/E) becomes outrageous.

- Christopher concludes this chapter with a lovely remark : “Investing is, arguably, more art than science, anyway. If investing well were all about statistics, then the best investors would be statisticians. And that is not the case. We’re looking for insights and wisdom, not hard laws and proofs.

Chapter 2 : Anybody can do this : True Stories

- Short chapter ; stories of people who did 100 bagger

Chapter 3 : The coffee can portfolio

-

As the name suggests, this chapter brings out the concept of Coffee can portfolio, which is covered to a great extent by another brilliant book “The Coffee Can Investing” by Saurabh Mukherjea.

-

The idea is simple: you find the best stocks you can and let them sit for 10 years. You don’t put anything in your coffee can you don’t think is a good 10-year bet.

-

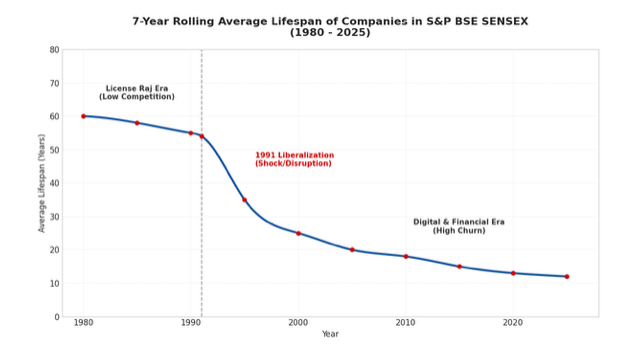

10-year is a good time. Atleast analyzing and pruning the stocks. While to get a 100 baggers, you have to let it go, you also have to embrace the reality that world s changing rapidly. The survival rate is low.

-

For example, take a look at the average lifespan of a firm in the S&P 500 index. It is now less than 20 years. In 1958, it was 61 years.

-

In indian context, Of the original 30 companies that made up the SENSEX in 1986 (base year 1979), **only 7 remain in the index today.

-

In the last 10 years alone, the SENSEX has seen a churn rate of roughly 50%. This means that if you look at the index today, half of these companies likely won’t be there in 2036.

-

-

Moral : Coffee can is a good approach as it eliminates short term action / activity. But it is not “buy-and-forget”, re-visit periodically.

Chapter 4 : Study of 100-Baggers

- A fellow named Tony at TS Analysis published one informal 15-page study called “An Analysis of 100-Baggers.”. Main takeaways he presented:

- The most powerful stock moves tended to be during extended periods of growing earnings accompanied by an expansion of the P/E ratio.

- These periods of P/E expansion often seem to coincide with periods of accelerating earnings growth.

- Some of the most attractive opportunities occur in beaten-down, forgotten stocks, which perhaps after years of losses are returning to profitability.

- During such periods of rapid share price appreciation, stock prices can reach lofty P/E ratios. This shouldn’t necessarily deter one from continuing to hold the stock.

-

Main Takeaway: Growth, Growth and more growth are what power these movers

-

Indian stock study also done with Motilal Oswal (to be written in separate article, these guys have brilliant analysis on their website). Their main summary for 100 baggers:

But there are other ingredients as well. “Our analysis of the 100x stocks suggests that their essence lies in the alchemy of five elements forming the acronym SQGLP,” they wrote:

- S—Size is small.

- Q—Quality is high for both business and management.

- G—Growth in earnings is high.

- L—Longevity in both Q and G

- P—Price is favorable for good returns.

Most of these are fairly objective, save for assessing management. “In the ultimate analysis, it is the management alone which is the 100x alchemist,” they concluded. “And it is to those who have mastered the art of evaluating the alchemist that the stock market rewards with gold.”

- Importance of Management is something that comes up in future chapters too.

Chapter 5 : The 100 Baggers of the last 50 years

- To get 100 Baggers, you need growth —and lots of it. Ideally, you need it in both the size of the business and in the multiple the market puts on the stock, as we’ve seen—the twin engines, as author call them.

Despite occasional exceptions, you do want to focus on companies that have national or international markets.

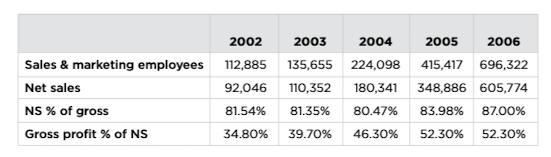

- From case study of Monster beverage, one key summary (and metrics to watch out for)

- Net sales grew to a larger percentage of gross sales. That reflects promotions (discounts) Monster no longer needed to offer, as Monster was now a well-known brand retailers wanted to carry.

- Gross profits as a percentage of net sales also increased as their copackers and distribution partners started to see them as a good customer and offer concessions to stay.

- In another analysis for Jeff Bezos / Amazon study, the analyst mentions

“At heart, he understands two things,” Thompson writes. “He understands the value of a business is the sum of its future free cash flows, discounted back to the present. And he understands capital allocation and the importance of return on invested capital.”

From Bezos’s 1999 shareholder letter: “Each of the previous goals I’ve outlined contribute to our long-standing objective of building the best, most profitable, highest return on capital, long-term franchise.”

From Bezos’s first shareholder letter, in 1997: “Market leadership can translate directly to higher revenue, higher profitability, greater capital velocity and correspondingly stronger returns on invested capital. Our decisions have consistently reflected this focus.”

- In case of Amazon, if one is analyzing stock, we need to add back CAPEX to arrive at the correct picture. Prof Aswath Damodaran also talks about this.

“Looking at Amazon’s reported operating income, it doesn’t look profitable,” Thompson continues. “On $88 billion in 2014 sales, Amazon earned a measly $178 million in operating income. That’s a razor-thin 0.20% operating margin.

“Adding back R&D, however, paints a completely different picture. In 2014, Amazon spent $9.2 billion on R&D. Adding that back to operating income, Amazon generated adjusted operating income of $9.4 billion in 2014. That’s an operating margin of 10.6%.

- Great study examples from Monster Beverages, Amazon, EA Sports, Comcast, Pepsi, Gilette. The author ends chapter with note from “One Up on the Wall Street” by Peter Lynch on the Importance of growth:

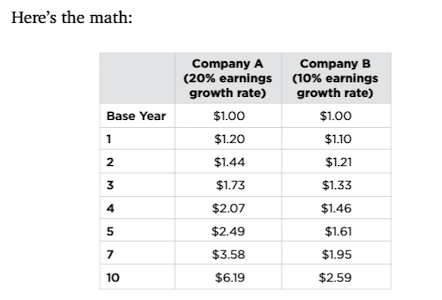

All else being equal, a 20 percent grower selling at 20 times earnings (a p/e of 20) is a much better buy than a 10 percent grower selling at 10 times earnings (a p/e of 10). This may sound like an esoteric point, but it’s important to understand what happens to the earnings of the faster growers that propel the stock price.

Chapter 6 : The Key to 100 Baggers

- This is transition chapter from examples so far to now going to nitty gritty of characterstick of a 100 bagger stock.

- “If a company has a high ROE for four or five years in a row—and earned it not with leverage but from high profit margins—that’s a great place to start,”. “So when you see a company that has an ROE of 20 percent year after year, somebody is taking the profit at the end of the year and recycling back in the business so that ROE can stay right where it is.”

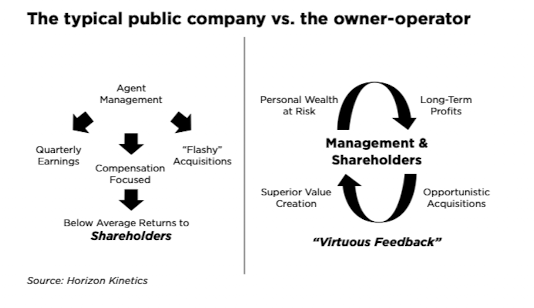

Chapter 7 : Owner - Operators : Skin in the game

So you have a situation where the stock is expensive and insiders are selling but ETFs are mindlessly buying more. There were other property companies owned by insiders that traded for half (or less) the valuation of Simon with twice the yield. “But because there’s not a lot of ‘free float,’ they’re being neglected,” Doyle said. “Those are the types of securities that we’re looking at and trying to include in most of our funds.”

- This chapter opens with a powerful point. One of the big contributors of stock moving up is Mutual Fund and ETF buying into it. But if a stock is owned largely by owners, the float (stock available in market to trade) would be less. So, less funds will go for it as they want to aquire a sizeable chunk. So the stock price will not be as appreciated or atleast not as quickly compared to other stocks which are more liquid.

- The Math: If a fund manages $10 Billion, a 1% position is $100 Million. If a company has a low “free float” (few shares actually trading), trying to buy $100M worth of stock would send the price skyrocketing before the fund could finish filling its order.

- The Exit Problem: Funds worry more about selling than buying. If they own 10% of the free float, they cannot exit the position quickly without crashing the stock.

- Result: They simply ignore these stocks. They must buy liquid, high-float giants even if they are expensive, because they can get in and out easily.

- If the stock has low float, it often gets excluded by Index (Nasdaq, BSE, NSE) . As the indexes calculates the market value by excluding the owner stocks. So, it also gets excluded from various ETF which are often passive funds and rule based (invest if it is in index)

- After this interesting insight, Christopher focuses that Owner operated after often high value, as they are owners so they take long term decision and also need not answer to the market in the short term

Chapter 8 : The Outsiders : The Best CEOs

The main idea is that these CEOs were all great capital allocators, or great investors. Capital allocation equals investment. And CEOs have five basic options, says Thorndike: invest in existing operations, acquire other businesses, pay dividends, pay down debt or buy back stock.

- This chapter presents research from the book “The Outsiders : Eight Unconventional CEO and their radically rational blueprint for success”. In the book, 8 successful CEO are analyzed (Including Jack Welsh and Warren Buffet). Thorndike writes each CEO understood that

- capital allocation is the CEO’s most important job;

- value per share is what counts, not overall size or growth;

- Long term value is determined by cash flows not reported earnings

- decentralized organizations release entrepreneurial energies;

- independent thinking is essential to long-term success;

- sometimes the best opportunity is holding your own stock; and

- patience is a virtue with acquisitions, as is occasional boldness.

- The chapter also goes into next candidates for such multi baggers. But this book is from 2015, and 10 years is a long time. So I would rather run my own research based on the principles.

Chapter 9 : Secrets of an 18,000 Bagger

-

This chapter starts with analysis of Berkshire Hathways whose stock rose 18000 times from 1965 to 50 years later. One of the key strength of Warren Buffet was he had free money from his insurance business where premium are paid first and then claim to be settled later. That gave them a float at very low (or negative) rate of interest. Berkshire had a negative cost of borrowing in 29 out of 47 years!!!

-

This chapter propose investing in other holding company models which can be a potential 100 baggers. The leaders of holding companies are, essentially, money managers with structural advantages in how they invest. They have permanent capital, unlike, say, a mutual fund manager who must deal with constant inflows and outflows. Holding companies also build businesses, as opposed to just buying and selling stocks.

Now that we have analyzed the gold standard of investing, let’s ask, is it possible that other Berkshire Hathaways exist? Let’s consider the holding company. A publicly traded investment holding company is one where the management team has wide freedom to invest as they see fit. They can invest in firms they own in the holding company. Or they can invest in outside firms. They can invest in public entities or private ones. They can even invest in different industries. The best-in-class example is the aforementioned Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. It owns publicly traded stocks such as Coca-Cola and IBM. But it also owns companies outright, such as GEICO and See’s Candies. It is involved in a mix of industries, everything from insurance to retail.

Berkshire Hathaway is the model investment holding company. It’s compounded value by almost 20 percent annually since 1965 (resulting in that 18,000-bagger). There are others, some of which we’ve mentioned: Leucadia National, Loews Corp., Brookfield Asset Management and Fairfax Financial Holdings. These are the most famous, with long track records of beating the market and compounding money year after year after year—for decades.

Chapter 10 : Kelly’s Heroes : Bet Big

- The idea of this chapter is simple : bet big on your best ideas.

- Kell’s formula is introduced in this chapter. John L Kelly (Bell Labs) sought an answer to a question. Let us say a gambler has a tipoff as to how a race will likely go. It is not 100 percent reliable, but it does give him an edge. Assuming he can bet at the same odds as everyone else, how much of his bankroll should he bet? Kelly’s answer reduces to this, the risk taker’s version of E = mc2: f = edge/odds.

- The maths doesn’t matter much for me, main takeaway is. I will work to select 10 solid stocks, and put 10% in each stock.

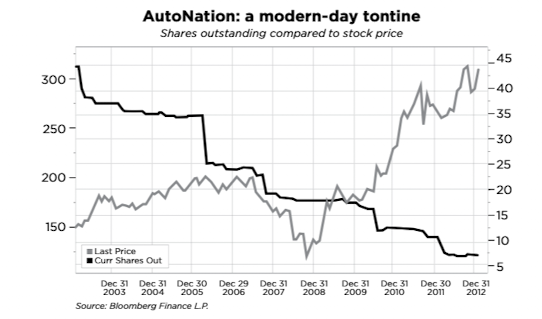

Chapter 11 : Stock Buybacks : Accelerated Returns

- A buyback is when a company buys back its own stock. As a company buys back shares, its future earnings, dividends and assets concentrate in the hands of an ever-shrinking shareholder base. Many companies are doing buybacks these days. In a slow- to no-growth economy, this tactic is becoming a more important driver of earnings-pershare growth.

- A powerful example is shared of a stock Autonation, which buyback its stock from 2000 onwards and retired the shares. Annualized, share grew more than 15% per year for 13 years.

- It is important what are the reasons for buyback. Bad reason is where the management wants to increase the value of its share, so it buyback from market and retire the shares, so value of remaining shares increase. As Warren Buffet puts in his 2000 letter to shareholders

There is only one combination of facts that makes it advisable for a company to repurchase its shares: First, the company has available funds—cash plus sensible borrowing capacity—beyond the near-term needs of the business and, second, finds its stock selling in the market below its intrinsic value, conservatively calculated.

- The reasoning is simple: if a fine business is selling in the marketplace for far less than intrinsic value, what more certain or more profitable utilization of capital can there be than significant enlargement of the interests of all owners at that bargain price? The competitive nature of corporate acquisition activity almost guarantees the payment of a full—frequently more than full price—when a company buys the entire ownership of another enterprise. But the auction nature of security markets often allows finely-run companies the opportunity to purchase portions of their own businesses at a price under 50% of that needed to acquire the same earning power through the negotiated acquisition of another enterprise. (emphasis added) When done right, buybacks can accelerate the compounding of returns.

- It’s a potential clue. When you find a company that drives its shares outstanding lower over time and seems to have a knack for buying at good prices, you should take a deeper look. You may have found a candidate for a 100-bagger.

Chapter 12 : Keep competitors out

- The most famous topic comes now - the discussion of “moat”. In the overwhelming number of cases, a company needs to do something well for a very long time if it is to become a 100-bagger. Persistence is as essential to a 100-bagger as gin to a martini.

- Various types of moats are captured

- You have a strong brand : Tiffany, Oreo etc. It may not allow for premium prices, but it inspires loyalty and ensures recurring customers. That is a moat

- It costs a lot to switch : Banks. They dont have much differentiating factors among them, but it is a hassle to switch. That is a moat.

- You enjoy network effect : So many internet companies are based on it. Microsoft, Whatsapp, Instagram, Facebook.

- You do something cheaper than everyone else. Walmart, Amazon…

- You are the biggest. Amazon, Reliance Jio - it prevents competitors due to cost of replication.

An interesting point here about the size of the firm relative to the market: “Imagine a market where the fixed costs are high, and prices are low. Imagine that prices are so low that you need 55% of the market just to break even. How many competitors will that market support? One. Not two, not three… one.” The firm that gets that 55 percent is in a commanding position. It can keep prices just high enough that it can keep others out and earn a good return. “What matters is the amount of the market you need to capture to make it hard for others to compete,”

- Maubossin did study on industry moats. One of the finding was some industries are better at creating values than others. But in every good and bad industry, there are ways to make money.

Mauboussin suggests creating an industry map. This details all the players that touch an industry. For airlines this would include aircraft lessors (such as Air Lease), manufacturers (Boeing), parts suppliers (B/E Aerospace) and more. This is beyond the scope of what an individual investor would do, but even though you aren’t likely to make your own industry map, it’s a useful mental model.

What Mauboussin aims to do is show where the profit in an industry winds up. These profit pools can guide you on where you might focus your energies. For example, aircraft lessors make good returns; travel agents and freight forwarders make even-better returns. Mauboussin’s industry analysis also shows that industry stability is another factor in determining the durability of a moat. “Generally speaking,” he writes, “stable industries are more conducive to sustainable value creation. Unstable industries present substantial competitive challenges and opportunities.”

- Last topic is mean reversion and importance of gross margin

gross margin is a good indication of the price people are willing to pay relative to the input costs required to provide the good. It’s a measure of value added for the customer. Not every company shows a huge gross margin. “Amazon’s are pretty mediocre,” Berry pointed out in an email to me, “but it is clear that the value added is in the selection and the convenience, not in the good itself (which could be found anywhere). But if you can’t see how or where a company adds value for customers in its business model, then you can be pretty sure that it won’t be a 100-bagger.

I’d sum up this way: It is great to have a moat, but true moats are rare and not so easy to identify all the time. Therefore, you should look for clear signs of moats in a business—if it’s not clear, you probably are talking yourself into it— you may also want to find evidence of that moat in a firm’s financial statements. ** **

Chapter 13 : Misclellaneous Mentation on 100-Baggers

-

Curious name of the title. Chris answers this in the first paragraph

Definition: men·ta·tion (men- t -sh n/) noun. technical. 1. mental activity.

In going back over the well-thumbed pages of my library of recent books on mental technique, I have come upon a number of provocative passages which I marked with a pencil but, for one reason or another, was unable to fit into any of my preceding chapters. I have decided to take up this group of miscellaneous matters here, treating the various passages in the order in which I come to them.

-

Some of the key tips from this chapter are:

- Don’t chase returns. An obvious tip, but re-iterating that chasing short term returns is useless unless you have an army of Quant people and resoruces to predict the stock price movement and what will happen in next 8-12 months. MOhnish Pabrai said it nicely:

When asked about this underperformance, he replied, “I think it is an irrelevant data point. There is nothing intelligent that one can say about short periods like 10 months. I never make investments with any thought to what will happen in a few months or even a year.” (emphasis added)

- Don’t get bored. Another common and accurate advice. Blaise Pascal famously said : “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone”. Same in stock market - people think action is a sort of progress. Though time and again analysis tells that approach like Coffee Can beats the market and with far less stress.

As the famed money manager Ralph Wanger used to say, investors tend to like to “buy more lobsters as the price goes up.” Weird, since you probably don’t exhibit this behavior elsewhere. You usually look for a deal when it comes to gasoline or washing machines or cars. And you don’t sell your house or golf clubs or sneakers because someone offers less than what you paid.

“Usually the market pays what you might call an entertainment tax, a premium, for stocks with an exciting story. So boring stocks sell at a discount. Buy enough of them and you can cover your losses in high tech.”

This last line is brilliant. World is obsessed with IT stocks, with the story of great gross margin, low distribution cost, new gen wealth creation. While all of that is true, end of day it is cash flow management and overall growth. As everyone is running after IT stocks, their Price can be very inflated. Where as “boring stocks” like Control Panel which makes printing solution for all industrial products and growing at 20% annually is available at 9x of earning.

- Don’t get snookered : avoid scams. Always look for incentive for management - short term incentives can lead to shortcuts, dishonest routes. Also, do not fall into charisma of CEO. This was mentioned in another study ; some great investors avoid meetings CEOs to not fall for “Halo Effect” or Personal bias.

- Warren Buffett Rarely relies on management meetings for investment decisions. He said : If I need to meet management to understand the business, I don’t understand the business.

- Charlie Munger was very skeptical of “CEO charisma.” He believed humans are terrible at judging integrity and competence from interaction. Preferred to judge by long-term behavior in filings and capital allocation.

- Peter Lynch, Joeh Greenblatt, Howard Marks all preferred looking at “what the company does”, documents, history and incentives.

- The research is damning. Jason Voss, CFA, explains why body language doesn’t work for detecting deception CFA Institute : humans perform barely better than random chance (about 54% vs 50%) at detecting lies through body language.

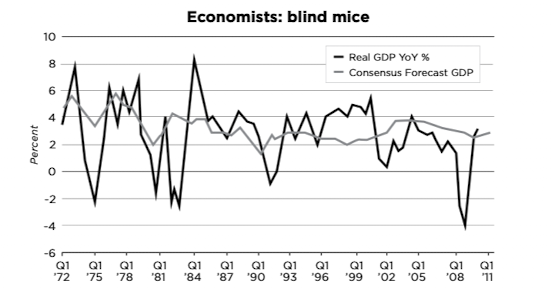

- Do Ignore Forecasters.

Many investors watch these estimates like hawks and rely on them in their buy and sell decisions. The problem is these estimates are wrong often, and by a wide margin. One large study covered nearly 95,000 consensus estimates from more than two decades. It found the average estimate was off by more than 40 percent!

Attempting to invest on the back of economic forecasts is an exercise in extreme folly, even in normal times. Economists are probably the one group who make astrologers look like professionals when it comes to telling the future…. They have missed every recession in the last four decades! And it isn’t just growth that economists can’t forecast: it’s also inflation, bond yields, and pretty much everything else.

- Warren Buffett remarked this in 1994 shareholder letter

We will continue to ignore political and economic forecasts which are an expensive distraction for many investors and businessmen. Thirty years ago, no one could have foreseen the huge expansion of the Vietnam War, wage and price controls, two oil shocks, the resignation of a president, the dissolution of the Soviet Union, a one-day drop in the Dow of 508 points, or treasury bill yields fluctuating between 2.8% and 17.4%…. But, surprise—none of these blockbuster events made the slightest dent in Ben Graham’s investment principles.

- Don’t get attached to an idea

People take easily, though, to big ideas: The new economy. Peak oil. The Chinese century. The Great Moderation. All of these things are just abstract ideas. They are predictions about how the world might look. But they are far from concrete experience—and hence likely to lead you astray. And each of the abstractions I mentioned has led investors astray. “Investment,” author John Train once wrote, “is the craft of the specific.” It’s about why A is a better investment than B. “It’s extraordinary how much time the public spends on the unknowable.” I’ve learned to identify and accept the unknowable. I’ve learned to distrust grand theories.

Chapter 14: In case of next great depression

- Small chapter, some good points. Particularly which sort of stocks do not make comeback from depression

- Stocks which were grossly overpriced to being with

- Stocks which suffers from permanent impairment - market changed fundamentally

- Stock which were massively diluted. Mostly when a company issues a bunch of new shares to raise money to cover losses or pay back debt. It is like adding water to your beer and sharing it.

Chapter 15 : 100-Baggers Distilled : Essental Principles

- We reached end of the book. In this chapter, Chris summarizes the discussion so far ; putting down the “essence” of the entire book. His (and also from an investor Charles Akre) approach is simple and easy to understand. He calls it his threelegged stool. He looks for •

- Businesses that have historically compounded value per share at very high rates;

- Highly skilled managers who have a history of treating shareholders as though they are partners; and •

- Businesses that can reinvest their free cash flow in a manner that continues to earn above-average returns.

- Akre (who has been investing since 1968) says

“Over a period of years, our thinking has focused more and more on the issue of reinvestment as the single most critical ingredient in a successful investment idea, once you have already identified an outstanding business.”

As an aside, you’ll note the absence of dividends. When a company pays a dividend, it has that much less capital to reinvest. Instead, you have it in your pocket—after paying taxes. Ideally, you want to find a company that can reinvest those dollars at a high rate. You wind up with a bigger pile at the end of the day and pay less in taxes.

- Another important point noted is ignoring the noise : How currency is acting, how interest rates are changing, how markets are reacting. That is why coffee can approach is proposed - find quality stock and trust that over larger time horizon, all the noise will not matter if growth is there.

- Some essential principles for finding 100 baggers:

- You have to look for them : “When looking for big game, be not tempted to shoot anything small”

- Growth, Growth and more Growth : This is the most repeated advice in the book. And worth repeating.

- So, you need growth—and lots of it. But not just any growth. You want value-added growth. You want “good growth.” If a company doubles its sales, but also doubles the shares outstanding, that’s no good. You want to focus on growth in sales and earnings per share.

- Earnings are the reported numbers, whatever they are. Earnings power, however, reflects the ability of the stock to earn above-average rates of return on capital at above-average growth rates. It’s essentially a longer-term assessment of competitive strengths.

- earnings may rise but the underlying earnings power may be weakening. For example, a company might have great earnings but a high percentage may come from one-off sources.

- Lower Multiples preferred : You do not want to pay stupid prices

- Let’s say you pay 50 times earnings for a company that generated $1 in earnings last year. Think what you need to happen to make it a 100-bagger. You need earnings to go up a hundredfold and you need the price–earnings ratio to stay where it is at 50. If the price–earnings ratio falls to 25, then you need earnings to rise 200-fold. Don’t make investing so hard.

- But on the other hand, you shouldn’t go dumpster diving if you want to turn up 100-baggers. Great stocks have a ready fan club, and many will spend most of their time near their 52-week highs, as you’d expect. It is rare to get a truly great business at dirt-cheap prices.

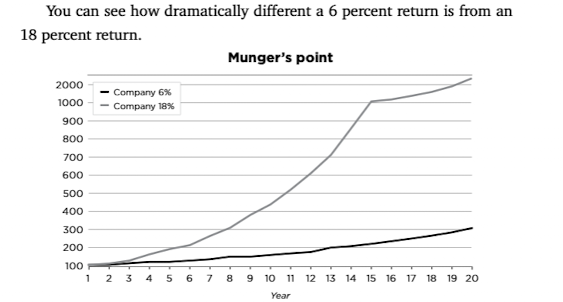

-

Charlie Munger said : “Over the long term, it’s hard for a stock to earn a much better return than the business which underlies it earns. If the business earns 6% on capital over 40 years and you hold it for that 40 years, you’re not going to make much different than a 6% return—even if you originally buy it at a huge discount. Conversely, if a business earns 18% on capital over 20 or 30 years, even if you pay an expensive looking price, you’ll end up with a fine result. “

-

At the end of 20 years, a company returning 18 percent on capital winds up with a pile nearly eight times larger. The lesson: don’t miss out on the chance to acquire great businesses at fair prices, and you can clearly see why in this chart.

- PEG Ratio : “One way to look at it is by using something called the PEG ratio,” Goodman suggests. “The PEG ratio is simply the (P/E Ratio)/(Annual EPS Growth Rate). If earnings grow 20%, for example, then a P/E of 20 is justified. Anything too far above 1x could be too expensive.”

- Economic Moats are a necessity

“Obviously,” Phelps concludes, “dividends are an expensive luxury for an investor seeking maximum growth. If you must have income, don’t expect your financial doctor to match the capital gains that might have been obtainable without dividends. When you buy a cow to milk, don’t plan to race her against your neighbor’s horse.”

- If dividends are a drag, borrowed money is an accelerant. A company that earns 15 percent on its capital could raise it to, say, 20 percent by taking on some debt. But this raises the risk of the stock too.

- Smaller companies preferred

- Apple, as great as it has been and is, won’t become a 100-bagger from current levels. The market values the stock at $750 billion. A hundredfold return from here would take it to $75 trillion. That’s more than four times the size of the US economy. It could be a good stock for some time yet, but the law of large numbers starts to work against you at some point.

- On the other hand, you shouldn’t assume you need to dive into microcaps and buy 25-cent stocks. The median sales figure of the 365 names in the study was about $170 million. This is unadjusted for inflation. It simply shows you that 100-baggers can start off as sizable companies. Sales of $170 million makes for a substantial business in any era.

- Owner-Operator Preferred

I would also remind you of something you should never forget: No one creates a stock so you can make money. Every stock is available to you only because somebody wanted to sell it. Thinking about that in the abstract, there seems to be no reason why you should expect to make money in a stock. But investing with owner-operators is a good reason to think you will. Because then you become a partner. You invest your money in the same securities the people who control the business own. What’s good for them is good for you. And vice versa.

It’s not perfect, but it’s often better than investing with management that aren’t owners. It helps solve the age-old agency problem. Seek out and prefer owner-operators.

- You need time : Use coffee can approach as crutch

- Deserves separate article. But theory is solid : do not try to time the market, but give your stocks time in the market.

- You need a really good filter

There is a world of noise out there. The financial media is particularly bad. Every day, something important happens, or so they would have you believe. They narrate every twist in the market. They cover every Fed meeting. They document the endless stream of economic data and reports. They give a platform for an unending parade of pundits. Everybody wants to try to call the market, or predict where interest rates will go or the price of oil or whatever. My own study of 100-baggers shows what a pathetic waste of time this all is. It’s a great distraction in your hunt for 100-baggers. To get over this, you have to first understand that stock prices move for all kinds of reasons. Sometimes stocks make huge moves in a month, up or down, and yet the business itself changes more slowly over time.

-

Luck Helps

- As with everything in life :)

To be sure, given our natural human commitment to the idea that we live in a rational world, we are inclined to think that there is always an ultimate reason…. All of this is perfectly natural but also totally futile. The only ultimately rational attitude is to sit loosely in the saddle of life and to come to terms with the idea of chance as such.

- You should be a reluctant seller. The right reasons of sell can be :

- You’ve made a mistake—that is, “the factual background of the particular company is less favorable than originally believed.” •

- The stock no longer meets your investment criteria.

- You want to switch into something better—although an investor should be careful here and only switch if “very sure of his ground.”

- It has gotten too expensive and you would not pick it again today if you do your study.

Further, you might point to periods where stocks got bubbly. In 1998 or 1999, Coke was trading for 50 times earnings. It was a sell then. But then again, would Coke have qualified for a buy based on our 100-bagger principles? I don’t think so. It was a sell even by those lights.

Favorite Quotes

-

“Every human problem is an investment opportunity if you can anticipate the solution,” the old gentleman told me. “Except for thieves, who would buy locks?”

-

Investing is, arguably, more art than science, anyway. If investing well were all about statistics, then the best investors would be statisticians. And that is not the case. We’re looking for insights and wisdom, not hard laws and proofs.

-

“In Africa, where there are no antelope, there are no lions” (Phelps, warning against the scam artists)

-

“Never invest in any idea you can’t illustrate with a crayon” – Peter Lynch

-

“When looking for big game, be not tempted to shoot anything small”. (On focusing the energy to find stocks which will move the needle)

-

“When you buy a cow to milk, don’t plan to race her against your neighbor’s horse.” (Phelps on folly of chasing dividends while still expecting growth on capital)